Archive

Theft? Madness is more like it

In the process of catching up on Google Reader post-convention, I came across this recent post from Robert Centor criticizing a recent NY Times Magazine article alleging that ‘America is stealing [sic] the world’s doctors.’ As Dr. Centor rightly points out, this is utter nonsense, on multiple levels. In this post, I want to address the aspect of the “foreign doctor/brain drain” question that applies to students like me; in the next I talk about physician and other “brain drain” more generally.

As a student at an LCME-accredited American medical school, I don’t fall into the “international medical graduate” (IMG) category in quite the same way as those in the article. And despite the fact that I’m “only” Canadian, I’m still foreign enough to have to figure out where my next visa will come from for residency, fellowship, and beyond. This post will not be an extended disquisition on the finer points of American immigration law and visa classifications (subjects with which I am far too familiar). You will, however, get a taste of how dysfunctional the American approach to foreign physicians is, especially at a time marked by widespread predictions of an impending doctor shortage.

Most public medical schools in the US and many private schools will not even consider non-citizen/non-permanent resident (foreign) applicants. Those of us who do get an offer somewhere find that we are not eligible for US government financial aid, and for a great deal of school-based aid as well. Despite this, we still benefit indirectly from taxpayer subsidies. Tuition makes up a minuscule fraction of medical school revenue; according to SUMS‘s tax returns, our tuition barely covers the costs of the medical education and educational technology support staff. Nothing more. The rest comes from patient care revenues and various grants, much of which in turn comes from the taxpayer.

After receiving a medical education at great personal financial cost (debt), yet one that’s also heavily subsidized by the US taxpayer, the expectation is that we go home. Or at least leave the country. Completing post-graduate training in the US requires finding residency programs that are willing to sponsor one of the two main types of visas that can be used for this purpose: the J-1 comes with a 95% iron-clad requirement to leave the US and work in one’s home country for two years upon completion of training before one can come back to this country; the H-1B comes with a 100% iron-clad time limit of six years (for reference, here is a list of residency length by field, not including sub-specialty fellowships). Even assuming one could find and be accepted into a program that will sponsor either visa, neither seems particularly conducive to “theft” of foreign physicians.

Unlike in medical school, foreigners in US residencies and fellowships often do benefit from direct US taxpayer subsidy, as Medicare pays for most residency positions, including salary and benefits. So what happens to foreigners who receive direct government subsidies to train in their specialty?

Again, the expectation is that we will go home (in the case of the J-1 visa), or at least leave the country (in the case of the H-1B). The United States is one of the few, perhaps the only, developed country that requires all long-term immigrants to be sponsored by an employer or a family member. There is no “points” system for independent applicants; no way for someone like me to prove that I’m smart, talented, possess in-demand skills, and probably ought to be allowed to stay indefinitely (not to mention the hundreds of thousands of dollars of subsidy I will have enjoyed by this point). More shockingly, there’s seemingly no desire on the part of the US government to hold on to the medical talent that it paid to develop.

What employer would sponsor a foreign physician? Moreover, what employer would sponsor any employee for permanent residence before at least a few years of full-time employment have passed? The H-1B comes with a six-year time limit; look at the length of various residencies at the link above. We’re short primary care physicians (3 years), yes, but we’ll be short general surgeons (5 years) and cardiologists (6 years) as well.

I, and those in my situation, are the lucky ones, comparatively. We don’t even have to jump through extra hoops for medical licensure and board certification the way “real” IMGs have to. It’s a wonder anyone manages this at all.

If the United States is “stealing” [sic] foreign physicians, it’s one of the most tragically/comically inept thieves I’ve heard of. Even in my “easy” case, after I will have spent 7+ years being educated at world-class American schools (11+ if you count college), the US is happy and indeed seemingly eager to see me go.

Some people would approach this conundrum entirely differently. They would argue that because foreigners in the American medical training process receive indirect and then direct government subsidies, the process should be closed to them in the first place. I understand the logic, but this strikes me as doubling-down on the foolishness of the current system. Getting into medical school and residency is frighteningly competitive. Being a foreigner only makes it harder. I make no claims as to myself, but one would therefore expect the marginal foreign applicant to be at least as good as the marginal American applicant… if not better. That some of them manage to stay in the US to practice medicine even in spite of the numerous hurdles along the way should suggest even more strongly that these are the people you want to hold on to.

Is it worth legislating science to have science-based regulation?

I’m no fan of quackery, whether it’s of the homeopathic, naturopathic, chiropractic, craniosacral, ayurvedic, or other woo-tastic flavour. I’m even less of a fan when it’s practiced by people with the letters MD or DO after their name. I think it’s deceptive and unethical to promote these unproven and often disproven practices to patients who come to you for professional advice.

Earlier this year, a Florida-based lawyer wrote a piece at SBM arguing that many quacktitioners are likely committing misrepresentation, in the legal sense, and possibly fraud in some cases. This was followed up with a series examining the background and historical legal status of naturopathy, acupuncture, and chiropractic, and now a proposal to enshrine science-based medicine in law.

Read the whole blog post to get a better sense for what’s proposed. The short version is that the proposed law would limit the scope of practice of licensed healthcare professionals by imposing a two-part test to be interpreted “according to its generally accepted meaning in the scientific community”:

- Is it (a diagnosis, treatment, procedure, medication, etc.) plausible, based on “well-established laws, principles, or empirical findings in chemistry, biology, anatomy or physiology?”

- If not, is it “supported, to a reasonable degree of scientific certainty” by either “good quality randomized, placebo-controlled trials” or “by a Cochrane Collaboration Systematic Review or a systematic review or meta-analysis of like quality.” If not… it’s verboten.[a trial that would pass the legal test would have a placebo control group, random assignment, no more than 25% attrition, at least 50 participants in each study arm, and publication in a “high-impact, peer-reviewed journal.”]

If so, has its ineffectiveness been “demonstrate[d], within a reasonable degree of scientific certainty” by the aforementioned controlled trials or Cochrane Reviews? If so, plausibility won’t save it from being forbidden.

With a scheme like this, the devil is usually in the details. In this case, I don’t think one needs to dive in too deep to realize why this is a bad idea.

Politics is a sausage factory, and the science-based medical community should be hesitant to get it unnecessarily involved. Just because something is wrong/a bad idea (like quackery) does not necessarily mean that it should be forbidden in an ideal world. Just because something wouldn’t exist in an ideal world (like quackery), it doesn’t mean that it’s a good idea to use the force of law to ban it.

As narrowly-tailored as it aims to be, this proposed law will have the effect of legislating scientific truth. What constitutes scientific consensus? Plausibility? A high-impact journal? Do we really want these and other scientific questions that are now debated in the literature and the public sphere to be decided definitively by judge and jury? Do we want to give the power to certify science to our legislatures? The same legislatures that have already licensed all sorts of quacks at the behest of their lobbyists?

Science is politicized too easily. Where a scientific conclusion is translated by law into an inevitable legal and policy consequence, the science will make a better political target than the legislation. See this piece on the Endangered Species Act for an example of what I mean.

The best of policies can be undone by politics. I’ve given a fair bit of thought to how one might design an anti-quack law that doesn’t have the potential to go drastically awry. I can’t, though this is likely a result of insufficient creativity on my part.

In general, there are two types of people in government. “Our people” and “their people.” Who they are may vary based on the party or based on the issue, but both types will always be there. And both types win and lose elections.

Here’s the question: do you trust “their people” to exercise good stewardship of scientific truth? If not, let’s not be too hasty in handing over the reins to the politicians.

Ethics of Physician Marketing (a.k.a “paging Dr. Spammer”)

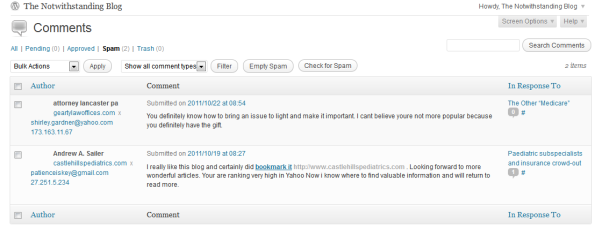

This was going to be a post about science-based medicine and the law. Really. I still might write it, maybe even tonight. But before I could get started, I cleared my comment spam. Among the usual expected unsavoury entities hawking the usual unsavoury wares, I found two recent spam comments from professionals who really should know better.

I think the law bloggers handle this better than we on the medical side do. There are plenty of social media evangelists in both fields who can be found online treating new technology as an end and not a means, promoting the ideal of “saying anything” over “saying something,” and generally clogging the ‘tubes with tweets, blog posts, and comments that barely even try to masquerade as anything beyond marketing. At least there are some lawyers out there willing to call “shenanigans” when they see them.

I have yet to see a physician call out his/her colleagues for scammy/scummy behaviour online. Not like some of the blawgs do. Take Ken and Patrick at Popehat, for instance. They’re brutal, and rightfully so. As another blawger, Eric Turkewitz, puts it: “when you outsource your marketing, you outsource your ethics“.

I am no luminary in the medical profession. Given that I blog pseudonymously, you can’t even be sure that I am a medical student. I claim no special authority to make pronouncements on medical ethics. I don’t need to. The following statement should speak for itself:

If you are a medical professional, comment-spamming blogs is not an acceptable marketing tactic. If you find yourself keeping company with SEO hucksters and vendors of penis-enlargement pills, you’ve made a wrong turn somewhere.Your online obligations don’t end at HIPAA.

Dr. Michelle Scott Tucker of Castle Hill Pediatrics, Carrollton, TX: you wanted search engine visibility. You got it.

These marketing shenanigans are undignified, unethical, and reflect incredibly poorly on the medical profession. I will not be associated with them. If you have a medical blog yourself, I hope you’ll join me. Make it clear to other physicians that indiscriminate spamming is no way to promote a practice. Call them out. Someone has to show them the error of their ways.

***

I will take another page from Popehat’s book and make the following offer to anyone called out for comment spam at this site:

“I will scrub this post of data identifying [you] and [your practice] on two conditions. First condition, [you] must make a sincere apology for [writing spam comments yourself, or] outsourcing [your] reputation and ethics […]. Second condition, [you] must provide emails or other documentation identifying the marketeer [you] hired who produced the comment spam and proving their responsibility for this, so that we can alter the post to call them out by name.”

My email is in the upper right-hand corner. You know how to reach me.

AAMC Follies: The New MCAT

The Association of American Medical Colleges made a splash this week with the release of preliminary recommendations for changes to the Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT), to take effect in 2015. The proposal getting the most press is the expansion of the scope of the test to include material from the social sciences, statistics, ethics, philosophy, “cross-cultural studies,” and other assorted non-science topics.

Given that the AAMC is one of the organizations raising the alarm about a looming physician shortage, it’s interesting to see that one of their responses is to ever-so-slightly raise the barrier to entry to medical school. That’s one heckuva cartel I’ve got on my side!

Of course, given the enormous mismatch between the number of medical school applicants and medical school spots, this change will not actually reduce the number of medical students (and as readers of this blog know, the real bottleneck is the number of residency slots). It will, however, increase the amount of time, effort, and money needed in order to meet the basic requirements for medical school admission. I suspect the test prep companies will fare especially well.

That said, I’m skeptical that the proposed MCAT changes are that worthwhile. I would be surprised if they do much, if anything, to address the concerns that seem to be motivating them. Here’s why.

1) Unless implemented very thoughtfully, inclusion of social science content will trivialize it by making it simply “another box to check” while studying. The USMLE has had limited success with this; can AAMC really do better?

The two recommendations from the the “MR5” report that seem to be driving much of the hubbub are these two:

3. Test examinees’ knowledge and use of the concepts in behavioral and social sciences, research methods, and statistics that provide a solid foundation for medical students’ learning about the behavioral and socio-cultural determinants of health.

4. Test examinees’ ability to analyze and reason through passages in ethics and philosophy, cross-cultural studies, population health, and a wide range of social sciences and humanities disciplines to ensure that students possess the necessary critical thinking skills to be successful in medical school.

I’m on record as a fervent supporter of making statistical fluency a pre-requisite for entry to medical school (or a college degree, for that matter). If this change leads to an increase in the statistical literacy of future medical students, that’s a plus. Similarly, as a former economics major, I am fully aware of the applicability of various social science concepts and techniques to the medical field. If a standardized test can assess the ability to analyze ethical and philosophical problems, so much the better (though I would imagine that it would be more likely to measure familiarity with the key buzzwords from each discipline).

The risk of including these topics on the MCAT is that by making these disciplines part of “just another hoop to jump through,” the test won’t be able to adequately evaluate the analytical ability and engagement with the material that the AAMC seems to value. Lest you dismiss this as an idle concern, here’s an actual question from a gold-standard review book for the US Medical Licensing Exam. Step 1 of the USMLE includes questions on sociocultural topics, ethical topics, the doctor-patient relationship, and the same “cross-cultural studies” that will soon be added to the MCAT.

A 40-year-old woman who recently had back surgery does not complain of pain, although magnetic resonance imagery (MRI) reveal re-herniation of the disc with significant nerve involvement. Of the following, this woman is most likely to be of

(A) Welsh descent

(B) Puerto Rican descent

(C) Greek descent

(D) Italian descent

(E) Mexican descent[(A) is the correct answer, because “Anglo Americans tend to be more stoic and less vocal about pain than to Americans of Mediterranean or Latino descent”]

(from Fadem, B. Behavioral Science in Medicine. LWW, 2004. p. 326)

The chapter for which this question was written is entitled “Culture and Illness;” it reads like a checklist of stereotypes about various ethnic and cultural groups. I have yet to figure out what real value this adds to my skills and maturation as a physician. If this sort of content is to be included on the MCAT, the AAMC will have to do a much better job for it to be worthwhile and meaningful.

2) The MCAT is not the tool by which to evaluate candidates’ personalities. That’s what interviews, essays, and recommendations are for.

The MR5 recommendations continue.

To help medical schools consider data on integrity, service orientation, and other personal

characteristics early in student selection, the AAMC should:

13. Vigorously pursue options for gathering data about personal characteristics through a new section of the AMCAS application, which asks applicants to reflect on experiences that demonstrate their personal

characteristics, and through standardized letters that ask recommenders to rate and write about behaviors that demonstrate applicants’ personal and academic characteristics.

14. Mount a rigorous program of research on the extent to which applicants’ personal characteristics might be measured along with other new tools on test day, or as part of a separate regional or national event, or locally by admissions committees using nationally developed tools.

Lots of people think medical schools should look “beyond test scores” and focus more on “personality” when judging applicants. Dr. Pauline Chen, writing at the New York Times, thinks so. The UChicago medical student with whom I discussed this on Twitter thinks so. Many of my classmates think so. I probably think so as well, but then I can’t pretend to know how these decisions are actually made in real life as it is.

The idea that mastery of social science content (or lists of stereotypes, as seen above) correlates meaningfully to personality is dubious, to put it charitably. Also, with pre-meds being who they (we?) are, I’m skeptical that any dedicated “personality test” section on the MCAT would last more than a couple of years without being dissected, gamed, studied-for, and meaningless as a gauge of an applicant’s character.

If it’s personality that you want in your medical students, the MCAT is not how you’re going to sort them. If the AAMC wants to create standardized tools to help medical schools evaluate applicants without actually needing to interview them (as recommendation #14 seems to imply), then they should go for it. I would think, though, that different medical schools might want different types of students. A one-size-fits all assessment might not serve every school’s needs equally well.

If the MCAT is over-weighted in the admissions process, then the real issue is how it’s used, not what it tests. It’s also worth pointing out that as long as medical school deans care about their US News & World Report rankings, they will place non-trivial emphasis on their entering students’ MCAT scores. That’s a pretty big counterweight to any movement to increase the weighting of “personality” in medical school admissions.

(Briefly discussed later in this post: what personality traits do we want in all of our medical students, why do we want those traits, and are medical schools really being flooded with so many applicants who lack them?)

3) Medicine is about service, but it’s still an applied science.

A common theme in the reactions of some of my classmates (and Dr. Chen’s NY Times piece) is that the MCAT and/or the medical school admissions process is too heavily focused on mastery of science. (Did I mention that I was an Economics major?). While the science content of the MCAT could certainly stand to be tweaked, I would hesitate to write it off completely. It is still the best predictor of success in medical school (where “success” is “not failing out during the preclinical years”), and the only standardized means of comparing science ability across applicants. What has helped me get through the first year of medical school has not been my social science background (though it has helped). It’s been the solid science foundation that I got in undergrad alongside my economics coursework.

If students want to help others and save the world without needing to take those pesky, difficult science courses, there are plenty of other career options open to them. Medicine still requires comfort with science, and that is the reality that we’re stuck with for the foreseeable future.

(For more on why science should not be viewed as an “obstacle” to medical school admission, I urge you to consult the ever-worth-reading David Gorski at Science-Based Medicine).

3a) Barriers to entry to medicine should not be arbitrarily and artificially increased, but it’s worth pointing out that medicine is a field that requires dedication… or at least that’s what they told me.

This is a minor point, but an important one. In my cynical estimation, there are three sorts of people who would want to become practicing physicians in this day and age: the naive; the passionate; and the crazy. Medical training is a long and arduous process, and the practice of medicine in the US isn’t about to get easier in our lifetimes. If someone is discouraged from going into medicine because of the MCAT… what would they do when confronted with Step 1 of the USMLE? The MCAT isn’t a personality test and shouldn’t be used as one, but at the same time, my inner curmudgeon has to question the bona fides of those who claim they would go into medicine “but for the MCAT.” When my classmates tell me that these proposed changes will make the MCAT more accessible to students who otherwise wouldn’t have taken it, there is a part of me that wonders whether that is really an unalloyed good.

4) Is there another agenda at play here? (WARNING: SPECULATIVE)

Even as the debate goes on between social science upstarts and science purists, between those who think that “personality” is over- or under-represented as an admissions criterion, one could be forgiven for wondering what the fuss is all about.

Medical schools aren’t lacking for applicants. There isn’t, to my knowledge, an epidemic of death, destruction, bad outcomes, or other horrors brought about by physicians insufficiently knowledgeable about the social sciences. I doubt that most medical school graduates are uncaring, unsympathetic, offensive brutes.

The main “problem” with medical students today, as far as I can tell, is that too few of them are willing to go into primary care careers. At least… some people see it as a problem with the students. I don’t.

There’s been a lot of attention focused on the primary care shortage over the past few years, some of it focused on delivery reform (think ACOs and PCMHs), and some of it focused on supply (e.g. the medical students). One noteworthy report authored by the American Medical Association in 2007 intimated that the primary care shortage could be solved by finding medical students who are more “service-oriented” and “altruistic,” better able to “be advocates for […] social justice,” and less “autonomous.” The report proposes including “social accountability issues” among admissions criteria.

Implicit in all of this is the assumption that the problem with the health care system, and the cause of the primary care shortage, is that we’re the wrong kinds of medical students. I’ve blogged about this report before, and why its premises and conclusions on this issue are utterly wrong; I don’t need to re-hash this here.

I can’t help but wonder how much of this line of thinking went into the recommended MCAT changes. No one — not the AAMC, not the many commentators whose responses I’ve read — has explicitly made this connection. But the rhetoric is the same. The implicit assumptions seem to be the same. The same misguided goals via the same misguided methods.

I hope I’m reading too much into things, but if not I can only despair at the solutions that organized medicine has found for our problems.

Heckuva cartel, eh?

AMSA Follies: Swagalicious

I’ve alluded to AMSA’s… interesting choices regarding who they will and will not take money from (or at least, who they will claim not to take money from). Here’s the long-promised photographic evidence: the swag I collected from conference exhibitors.

What you’ll find below the cut includes:

- A pamphlet, a bag, and some pens from Medical Protective, a professional liability insurance company owned by Berkshire Hathaway.

- A Merck Manual (yes, that Merck… the one that makes all these ”pharms” of which AMSA claims to be ”free”).

- Materials from various academies of quackery (as seen earlier).

- A pen, a magnet, and some other swag from the FDA.

- Application forms for various forms of insurance/consumer credit provided by or through AMSA.

- Some stuff from banks.

- Swag NOS.

AMSA Follies: Marketing Misadventures

[My efforts at live-blogging/tweeting have been foiled by the fact that this conference occurs two levels below ground where there is no connectivity of any sort. I guess this means the hotel has me on tape delay…]

The first talk of the morning was by a second-year medical student (Shahram Ahari, UC Davis)who spent some time as a sales rep for Eli Lilly after graduating from Rutgers. He went into sales because he thought it would be an opportunity to connect with clinicians at an intellectual level and discuss the science. Because that’s what a private-sector sales job is all about. Needless to say, he was somewhat disillusioned, especially upon finding that most of his salesforce colleagues weren’t scientists, but… salespeople. Go figure.

The presentation wasn’t irrationally hostile to pharm companies, though I might have caught the suggestion at the end that physicians have an “obligation” to vote the interests of their patients. He explained the many ways in which pharm sales people use the same techniques employed by salespeople in any industry: appeals to emotion backed up by data about the client that is never overtly mentioned.

The discussion was focused almost entirely on the prescriber-marketing interface; I was hoping for some evaluation of the appropriate nature of researcher-industry relationships, which is where (in my view) the controversy is much hotter. Nonetheless, it was an entertaining talk that explained the psychological basis behind all sorts of marketing techniques such as giving away free stuff…

Oh, right! Free stuff! AMSA might claim to be pharm-free, but a quick visit through their exhibition hall revealed a whole host of characters whose money AMSA was more than happy to accept in exchange for a booth. Some of these groups are more savoury than others.

Details to come… truly extraordinary.

![notwithstandingblog at gmail [dot] com notwithstandingblog at gmail [dot] com](https://notwithstandingblog.files.wordpress.com/2010/04/contact.png) notwithstandingblog at gmail [dot] com

notwithstandingblog at gmail [dot] com

Foreigners are people too

This is the second of two posts prompted by Dr. Robert Centor’s critique of a recent New York Times Magazine article accusing America of “stealing [sic] the world’s doctors.” In the first post, I show how US immigration policy for physicians is a boondoggle of near-comedic proportions that doesn’t even constitute an effort at “theft,” given that it’s hard-pressed to hold onto me after I graduate (as I explain, I should be one of the easier doctors to “steal”).

Now let’s look at the counterfactual situation. Suppose the it were actually easy and straightforward for physicians to immigrate to the US (or to remain, in my case), gain licensure, and be certified in their specialties. Suppose the immigration and licensure systems were designed with this very goal in mind. Would this be a bad thing?

The conventional wisdom is that the emigration of skilled professionals from less to more-developed countries is bad for the less-developed countries: this process is often referred to as “brain drain.” Critics argue that “brain drain” harms poorer countries by preventing the development of local talent, skills, and professionals that are often sorely needed. They also point to the fact that many countries subsidize education at least to some extent, only to see the investment in their citizens’ human capital slip away beyond their shores.

The conventional wisdom is wrong. As the 19th century economist Frederic Bastiat pointed out, it is best “not to judge things solely by what is seen, but rather by what is not seen.“

What is “not seen” when it comes to emigration of skilled professionals? Networks of diaspora spread ideas and expertise, strengthen economic and social ties between countries, promote peace, and promote advances in the standards of living both at “home” and “abroad.” Emigrants usually earn much more in their new country, and their remittances home are not only better able to support their family and community, but are often enough (over a lifetime) to dwarf the amount their home government spent on their educations. The option of emigration to higher-income countries creates incentives for poor countries to invest in education, and for their citizens to take advantage of it. In short, emigration of skilled professionals to richer countries enhances their productivity, which in turn has positive effects for their home country, their adopted country, and all of us along the way.

Yet even this analysis misses the fundamental point. To insist, as the New York Times does, that foreign physicians somehow “belong” to their home countries is to objectify and commodify them. When you think about it, it’s a remarkable assumption for anyone to make. Foreigners are people too. We’re not chess pieces to be pushed around a board, traded for promises of foreign aid, trade preferences, or anything else one might imagine. The Canadian government has no more claim on me and my career than the American government does on anyone who has ever attended a public school in this country.

This is a universal principle. I don’t care how poor the country is, no government can claim to “own” its people in this way. It’s absurd to suggest that the United States government should alter its immigration policy to cater to other countries’ desire to engage in this form of subtle repression, and even more absurd to think that this would actually benefit anyone.

Physicians who voluntarily leave one country for another in the hopes of making a better life are not “being stolen.” Not unless you think they’re owned by someone other than themselves. At its core, that’s what this discussion is all about. And that’s why, in my mind, there should be no ambiguity as to the right conclusion.